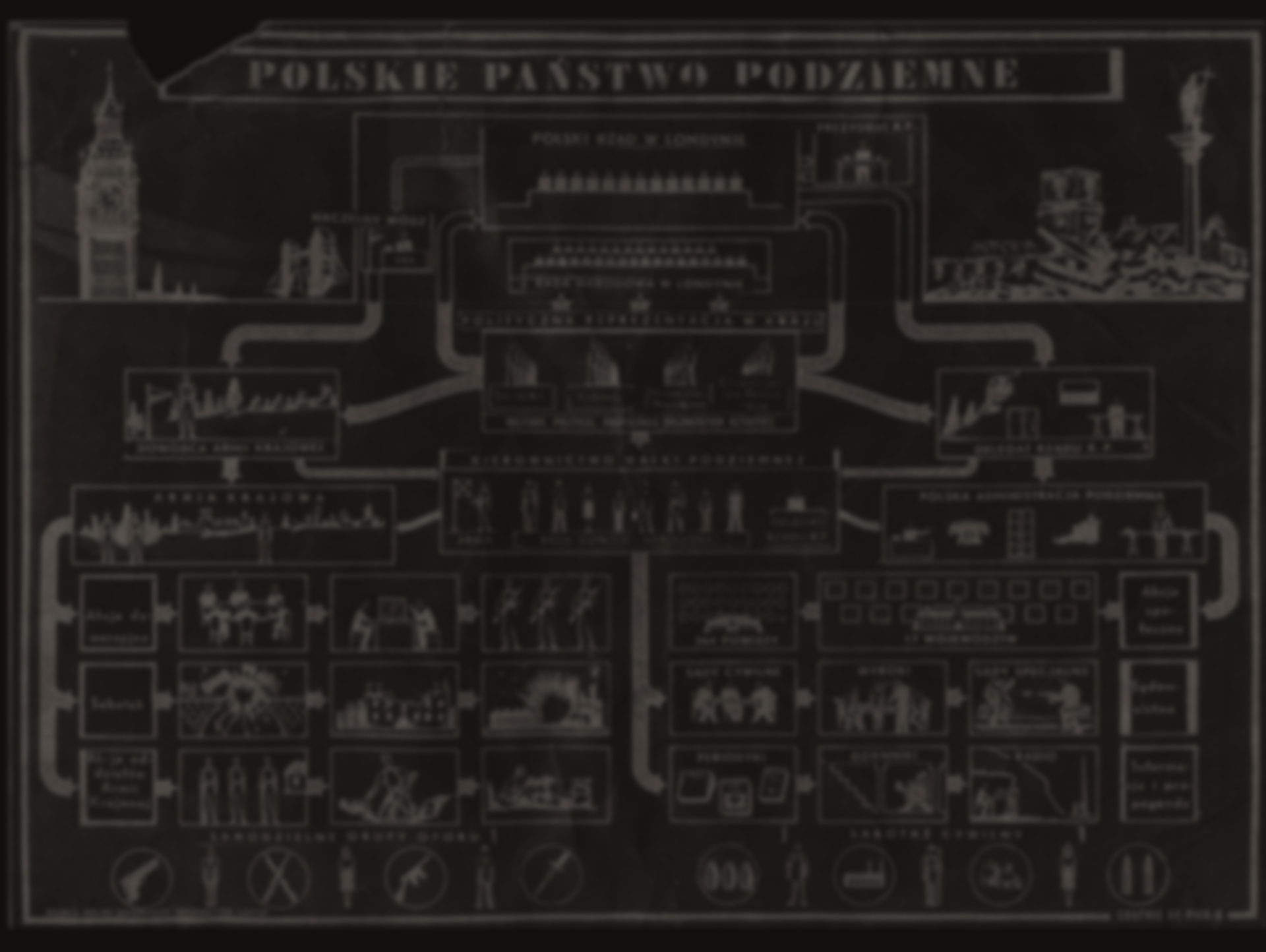

DIAGRAM OF POLISH UNDERGROUND STATE

DIAGRAM OF POLISH UNDERGROUND STATE

[…] My chief work was concerned with the creation of a special center in the Underground, the office of the ‘plenipotentiary of the government.’ The creation of this office was contingent upon the acceptance of two basic principles: first, that no matter what course the war might take, the Poles would never agree to collaborate in any way with the Germans. Quislings were to be eliminated at all costs.The second principle was that the Polish state was to be perpetuated by the underground administration which would be synchronized with the government-in-exile.

The so-called ‘stiff attitude toward the occupants’ simplified the problem of obtaining the consent of the people to the authority of the underground state. The German occupation was never recognized by the Polish people, and there could be no doubt on this score because, in Poland alone of all the occupied countries, there never appeared anything remotely resembling a legal or pseudo-legal body composed of Poles and collaborating with the Germans. Indeed, in all Poland, not a single political office in the German controlled administration was ever held by a Pole; not a single head of any province was Polish.

[...]When the Underground attained the peak of its development, the problem of collaboration was defined in precise terms as, in ordinary circumstances, a civil crime would be defined, and punishment was meted out in accordance with the ability of the Underground to carry out the sentences entailed.

According to the tradition handed down from the Polish insurrections against Tsarist Russia in 1830 and 1863, the place of the government should have been directly within the underground movement. It was realized, however, that such a government would have to be secret and anonymous. Consequently, Poland would have no contact with her Allies and no method of pursuing a foreign policy. If this government were liquidated, moreover, it would be impossible to appoint a new government. Chaos would result. The final factor that determined the decision that the government should remain in exile for the duration was the realization that the Underground required a method for maintaining the technical continuity of the organization.[...]

Steps had to be taken to reassure each party in the Underground that the administration created in the Underground would not be inimical to its interests and principles.[...]

Urgent stress was placed on the responsibility of these officers to all the political parties that were to constitute an underground parliament and control the personnel and budget of the administrative branch.

J. KARSKI, STORY OF A SECRET STATE, P. 144 -147

READ ALSO

COMMENT

In the face of aggression by both Germany (September 1st 1939) and the Soviet Union (September 17th 1939), the President, the government and the Commander-in-Chief crossed the border into Romania. Due to pressure from the Third Reich and the Soviet Union, they were interned by the Romanian authorities. Invoking his constitutional powers, President Ignacy Mościcki designated as his successor Władysław Raczkiewicz.

MP, 1939, No. 214-217

Pursuant to Article 24 paragraph. 1 of the Constitution, I appoint Władysław Raczkiewicz, the former Speaker of the Senate, to succeed the President of the Republic of Poland in the event the office of President is vacated before the conclusion of peace. [...]

President of the Republic of Poland (-)

Ignacy Mościcki

source: Historia ustroju i prawa w Polsce 1918–1989. Wybór źródeł [History of the Political and Legal System in Poland, 1918–1989. Selected Sources], Warsaw 2006, p. 183.

READ ALSO

Information about the death of General Sikorski

COMMENT

General Władysław Sikorski is dead

On July 5th, the plane carrying Prime Minister Sikorski crashed during take-off on a flight from Gibraltar to England. The Prime Minister was returning to England from an inspection of Polish troops in the Middle East. Along with the Prime Minister, also killed in the tragic accident, were Chief of Staff Gen. Klimecki, the British liaison officer to the Prime Minister – Minister of Parliment Victor Cazalet, the Prime Minister’s daughter Zofia Leśniowska, and four Polish officers.

The government under the leadership of President Raczkiewicz met in special session shortly afterwards. President Raczkiewicz temporarily assigned Stanislaw Mikołajczyk to perform the duties of the Deputy Prime Minister. Minister of Military Affairs Gen. Marian Kukiel was chosen to act as Commander-in-Chief.

The President of the Republic of Poland called for a two-week period of national mourning.

“Information Bulletin”, No. 27 (182) in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków t. II [The True Story of the Poles, Vol. 2], Warsaw 1999, p. 1204.

Despite military defeat in 1939, the Polish state survived. The government formed in Paris on September 30th 1939 by President Władysław Raczkiewicz was internationally recognized as Poland’s legitimate government. In December 1939, the Polish government moved its headquarters to Angers, and in June 1940 to London. The first Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile was Gen. Władysław Sikorski, the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces. In July 1943, he was killed in a plane crash over Gibraltar. After the General’s death, Stanisław Mikołajczyk was appointed Prime Minister, and held this office until November 1944. After Mikołajczyk’s resignation, Tomasz Arciszewski became the new Prime Minister.

I spent most of the next six days in Paris working on this report. After I was through, I called Sikorski’s secretary again for an appointment. Kulakowski requested me to come to our embassy to meet him. I went with considerable excitement. Sikorski was highly regarded in Poland. He was the kind of man whom Poles call a ‘European,’ a man of broad culture. He was a great general, a convinced liberal and democratic statesman who, during the Pilsudski regime, was strongly in opposition. After the catastrophic defeat of Poland, we put all our hopes in him.

In the anteroom of Sikorski’s office in the embassy, I was astounded to meet Jerzy Jur, my friend from Lwow. We greeted each other with delight. He told me about his escape and then we both became embarrassed as the conversation turned to what our present occupationswere. Neither one of us was allowed to discuss our status and so, amusingly enough, we had to fence with each other. Later, we realized that we were both going to Poland, but unfortunately we could not discuss it. We exchanged addresses, however, and I went in to see General Sikorski.

Sikorski was a man of about sixty, tall and upright in bearing. He appeared to be in excellent health. His manner was polished and his gestures had become slightly Gallicized. During the period of his opposition to Pilsudski, he had spent many years in France, becoming deeply attached to her. Since the First World War he had been particularly close to the French General Staff and many leading French military men held him in high esteem as a strategist. He permitted me only a very brief conversation in his office and told me to meet him in the Café Weber for lunch on the following day. We met in the restaurant lobby; a secluded table had been reserved for us. We sat down and I ordered a drink. Sikorski excused himself.

‘Lieutenant Karski, permit me, please, not to join you in drinking,’ he said with an apologetic smile, ‘I am too often compelled to drink at diplomatic banquets and I am usually sick afterwards.’ He was extremely polite and affable, inquired a good deal about apparatus of a state must be created and maintained at all costs, no matter how crude it is.’ Furthermore, he pointed out that the army must be unified into a whole rather than exist as an aggregate of atomic bodies, and stressed that the military had to be integrated completely into the social and political structure. ‘It cannot be allowed to remain distant or isolated. The liaison must be complete and conditions of mutual responsibility must be made to prevail,’ he insisted, laying his finger unerringly on the weak spot. An image came to my mind of the scowling, beetle-browed countenance of the military leader in Lwow and my nod of agreement was unusually emphatic.

‘But the army,’ General Sikorski went on, ‘shall never be allowed to interfere in political life. We have had enough of that. It must be the armed force of the people, animated by the ideal to serve the people, and not to rule them, not to lead them.’ I brought up one of the thorniest questions the Underground had to face. ‘How literally should we interpret our principle of “non-collaboration”?’ I asked. ‘Sometimes it may be valuable for us to have our men infiltrate into the German organizations. Can we do that?’ Sikorski’s reply was wholly characteristic.

‘The Poles in Paris,’ he said with a touch of irony, ‘live very well. We eat good food, sleep in comfortable quarters, and have few personal worries. We can’t tell the suffering and starving people in Poland what to do. I would not dream of attempting to impose my will. It would be immoral. The function of the government in France is merely to take care of their interests abroad. If they want my suggestions on the matter, I would say that any collaboration is unfavorable to our international political status. They shall do whatever they judge necessary. As long as we are abroad, we cannot issue orders to the Polish people. Our task is to fight the Germans. But please tell them to remember our history and our traditions. Tell them that we here are sure they will choose the right way.’ On the subject of a delegate of the government who would be the chief of the underground administration and the link between the Underground as a whole and the government in France, Sikorski again stressed that what the Poles inside Poland wanted was of primary importance.

‘If any individual has the support of the people in Poland and they desire him as our delegate,’ he said, ‘then he shall have our support, no matter what his political convictions are.’

Karski About The Last Meeting With Władysław Sikorski

One day [in May 1943] I received a sudden call from General Sikorski. I went to his office and he gave me my orders. ‘You are going soon to the United States,’ he told me abruptly, ‘in the same capacity as here. You have no further instructions of any kind. Our Ambassador, Jan Ciechanowski, will put you in touch with prominent Americans. You will tell them what you have seen, what you have been through in Poland, what the Underground has ordered you to tell the United Nations. Remember one thing, under no circumstances are you to make your report dependent on the political situation or the type of people you address. You will tell them the truth and only the truth. Answer all questions that do not endanger your comrades and harm the Underground. Do you understand what I expect from you? Are you aware of how firm my faith is that you will speak impartially?’5 ‘Thank you, sir, yes,’ I replied, ‘I want to tell you how grateful I am for your confidence and for the way you have treated me.’ When I left this man I had no idea that I would never see him again. It was the greatest of all shocks when a few weeks later the news of his tragic end was flashed around the world. General Sikorski died as a soldier on duty, in an airplane crash near Gibraltar.6 We Poles had no luck in this war.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, , p. 417

READ ALSO

COMMENT

Beginning in September 1939, Polish Army units began to be formed on French soil. These units were comprised of Poles living in France and neighboring countries, and soldiers arriving from Poland. The Polish military units in Western Europe were formed on the basis an interallied agreement with Britain and France. When the war ended in 1945, the Polish Armed Forces in the West numbered roughly 250,000 soldiers.

On November 7th 1939, Władysław Sikorski, having been nominated by the President of Poland, assumed the position of Commander-in-Chief (and simultaneously of Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile). After Sikorski’s tragic death, Gen. Kazimierz Sosnkowski was appointed to the position of Commander-in-Chief. He served in this role until September 30th 1944.

After the resignation of General Sosnkowski, General Tadeusz Komorowski became Commander-in-Chief, having been appointed to the position during the Warsaw Uprising (August 1st – October 2nd 1944). He held this position until November 1946, when Poland’s military forces were reorganized. From October 5th 1944 until May 5th 1945, when General Komorowski was in German captivity, the duties of Commander-in-Chief were assumed by General Władysław Anders.

It was through one of the political parties, the National Party, that I received my second mission. It was arranged for me to go to Lwow, perform a number of functions there, and afterwards make an attempt to reach France and contact the Polish Government in Paris and Angers. Orders had come from General Sikorski and the Polish Government for all young Poles to try to escape to France. These orders applied particularly to pilots, mechanics, sailors, and artillery men, the last category being the one to which I belonged. If I reached France, I would be performing a double task: obeying this order and carrying out an underground assignment.

J. Karski Story of a Secret State, p. 93

The next day I ran into Kot in the Café de la Paix. I gathered that he frequented the place with his customary regularity. In Cracow, he had visited a certain café with such mechanical regularity that his students had nicknamed it the Café Kot. We discussed my conversation with General Sikorski.

Kot was in complete agreement with the proposals. He ventured the opinion, however, that Poland would be occupied for a long time and that the Underground must prepare for a long struggle. He then suggested that I get in touch with General Sosnkowski, the chief of the Military Underground, for a conference.I called Sosnkowski’s adjutant, who arranged a meeting in a modest bistro. Sosnkowski is a tall, tough, military type of a man, about sixty-five years of age. He has unusually piercing blue eyes beneath bushy eyebrows. He was Pilsudski’s chief of staff when Pilsudski organized the underground forces against our oppressors before the First World War. His old training had never deserted him and he still had conspiracy in the very marrow of his bones. The first thing he did was to snap out a reprimand for calling his adjutant so freely. Didn’t I know that telephones could be tapped?

I accepted the rebuff without answering. He asked me about generalconditions in Poland and offered little or no suggestion while I recited the social and civil problems. His métier was military affairs. His opinion was also that Poland would be occupied for a long time. He told me that it was highly important for the Polish people to realize that this was not an ordinary war and that when it was over, all life would be changed and modified.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 134-135

READ ALSO

Communiqué of the Government Delegate for Poland

COMMENT

It is hereby announced that, in accordance with the decision of the Government of Poland, a Council of National Unity has been established in Poland. The Council of National Unity includes representatives of democratic Polish independence organizations which are actively involved in the struggle against the occupation forces and remain loyal to Poland’s civil and military governing authorities based in London, and their counterparts in Poland.

Due to the creation of the Council of National Unity – the previously existing Home Political Representation (formerly known as the Political Consultative Committee) will cease to exist

“Information Bulletin”, No. 3 (210) 1944, in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków. Ilustrowane wypisy źródłowe 1939-1944. t. II [The True Story of the Poles. Illustrated excerpts of sources, 1939-1944, Vol. 2], Warsaw 1999, p. 1443.

The first provisional representative body for Poland’s political parties was created on October 10th 1939 under the name of the Main Political Council of the Service for Poland’s Victory. It was composed of representatives of the four major political parties in pre-war Poland. After the arrest of the members of the Council, the Political Consultative Committee was established in February 1940, which the Polish government-in-exile recognized as the country’s political representation. Part of its mandate was to decide on political, economic and social issues. The Committee played an important role in the formation of the Underground, inspiring passive resistance and other forms of civil resistance. In 1943, it was transformed into the Home Political Representation. In January 1944, a Decree of the Government Delegate for Poland created the Council of National Unity, a consultative and advisory body of the Delegate. The underground Polish Parliament was composed of 17 representatives of the country’s political parties. The Chairman of the Council of National Unity was Kazimierz Pużak.

The third branch was called the Political Representation and constituted the parliament of the Underground.

Each of the four major political parties conducted, on their own initiative, many of their activities within the framework of the Underground. They had the right to engage in autonomous propaganda, political and social activity, and resistance to the occupant. But the representatives of these four parties constituted one official body, and to it were responsible both the Chief Delegate and the Commander-in-Chief of the Army.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 256.

READ ALSO

COMMENT

Government Delegate for Poland (given the rank of Deputy Prime Minister in 1944) was a position created in November 1940 to coordinate political life in Poland and maintain communication with the government. In cooperation with the country’s political representatives, he took decisions on political, economic and social issues. His job was to maintain the continuity of state institutions and ensure the state’s proper functioning. The first Government Delegate for Poland was Cyril Ratajski, appointed in December 1940. Due to failing health, he resigned in September 1942. His successor as Government Delegate was John Piekałkiewicz, who held the office until February 1943, when he was arrested and murdered by the Gestapo. In March 1943, the office of Government Delegate was assumed by Jan Stanisław Jankowski. He held this position until his arrest by the Soviet NKVD in March 1945.

The administrative branch was composed of the Chief Delegate of the Government and the Regional Delegates. Under their supervision twelve departments functioned, each one of which had a director who was the counterpart of a Minister of the Polish government-inexile, now in London, such as the Director of the Interior, Treasury, Education, etc.

The primary duty of this branch was to organize and maintain the autonomous and secret deputy administration of the country. The attitude of ‘not noticing the occupant’ had prevailed. The Poles had refused any part in the political administration of the German General Government and the edict had been issued that not a single law or decree of this agency was to be obeyed. The result would have been a condition of chaos, and the authority of the Secret Deputy Administration was established to bring control over the country. This administration exercised compulsion on the populace to a much greater degree than the Nazis could with all their brutal measures. In each county, city, and community, there was an official who, invested by the full authority of the state, issued decrees, and contacted the people. These persons were also designated to be ready the instant the country was cleared of the invader, to take over as a complete, democratically chosen administration, fully capable of managing the affairs of the country.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 254-255

READ ALSO

General Sikorski’s order

COMMENT

[…]

ORDER PLACING ALL MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS IN POLAND UNDER HOME ARMY COMMAND

[…]

1) All military organizations in the country which aim to participate in the fight against the enemy or act as a military auxiliary are to be placed under Home Army Command.

2) Depending on the nature of the organization, the Home Army Commander:

a) will either order the total or partial incorporation of the organization into the Home Army

b) or leave it in its current form, specifying its degree of subordination [...]

5) Military organizations that do not submit to being placed under Home Army command will not be recognized by the Polish government. [...]

Commander

And

Minister of Military Affairs

Sikorski, Lt. Gen.

source: Armia Krajowa w dokumentach 1939-1945, t. II [Home Army in Documents 1939-1945, Vol. 2], Szczecin 1989, pp. 295-296.

The commanders of underground military organizations operating inside occupied Poland were under Home Army command and remained politically loyal to the Government Delegate.

The founder and commander of the Service for Poland’s Victory (Polish: Służba Zwycięstwu Polsce - SZP), the first military organization inside Poland after war broke out wasgen. Michał Tokarzewski – Karaszewicz. In November 1939, the Polish Victory Service was replaced by the Union for Armed Struggle (Polish: Związek Walki Zbrojnej - ZWZ). The Commander of the organization was gen. Kazimierz Sosnkowski, who was in France. In June 1940, Gen. Stefan Rowecki became the Commander of the ZWZ (and later of the Home Army, which succeeded it in February 1942), and after his arrest in June 1943, Gen. Tadeusz Komorowski became the Commander of the Home Army. After the Warsaw Uprising, Gen. Komorowski, who was now Commander-in-Chief, was placed in captivity by the Germans. On January 19th 1945, the position of Commander-in -Chief was assumed by Gen. Leopold Okulicki, who issued an order for the Home Army to be dissolved.

The military branch was organized as a domestic army. The Commander-in-Chief of this army and his regional commanders had all the rights and prerogatives of army commanders with regard to the population of a war zone. They could issue military edicts to guide the behavior of the population, and requisition men for necessary war work. Each soldier in the army had all the rights and duties of a front-line combatant, even including the traditional one that all time spent on the front lines counted double toward all benefits such as veteran’s pensions, priority rights, and civil service.

The Commander-in-Chief, although this was not known to the public, was allocated a special power by a decree of the President. He was authorized to call a partial or total mobilization of all Poles the moment the Polish Government, acting in concert with the other Allied governments, gave the order for an open, universal uprising against the German occupants. The work of the Home Army was divided into two parts: Command included propaganda, political diversions against the occupant, organization for the general uprising, and tasks undertaken in cooperationwith the political and administrative branches; the other was devoted to the daily struggle and included sabotage (activity against the German civil and industrial war machine), diversion (direct activity against the German Army, its communications, supplies and transport), military training, etc. In addition, it collaborated with the units that operated in the areas that had been incorporated by force into the Reich and Soviet Union.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 255-256

READ ALSO

The Home Army swears an oath

COMMENT

from order No. 58 of Army Commander Brig. Gen. Stefan Rowecki, dated February 22nd 1942

[…]

Before Almighty God – and the Blessed Virgin Mary, Queen of the Polish Crown – I place my hand on this Holy Cross, a sign of the Passion and Redemption, and I swear that I will faithfully and unswervingly uphold the honor of Poland and will always fight with all my strength, and even sacrifice my life, for its liberation from bondage. I will obey all orders and maintain confidentiality, no matter what may happen.

[...] In taking this oath, Protestants leave out the words between the dashes.

in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, [The True Story of the Poles, Vol. 1], Warsaw 1999, p. 506.

The armed forces of the Polish Underground State, operating covertly within occupied Poland. It was the largest underground army in occupied Europe, numbering roughly 380,000 soldiers at its peak.

By order of the Commander-in-Chief on February 14th 1942, previously existing military formations were merged to form the Home Army, with a Commander leading the organization. The Home Army was organized into sections, which included the Directorate of Diversion (also known as Kedyw) and the Bureau of Information and Propaganda (BIP). The first unit was responsible for carrying out sabotage and diversion. The job of the BIP was to inform the public about the activities of the Polish government in London, combat German propaganda, and document the actions of the occupation forces. It also organized underground reserve officer cadet schools and non-commissioned officers’ training schools.

The Allied staffs had high praise for the work of the Home Army’s intelligence network, which also conducted operations in the German Reich and the Soviet Union – among the successes of Polish intelligence was its smuggling out drawings and components of the German V-1 rocket. The Home Army also organized the clandestine production of weapons.

The publishing activities of the BIP were carried out by the Secret Military Printing Works (created in March 1940), which consisted of a network of clandestine printing houses and other print shops.

The main purpose of the Home Army was to organize a popular uprising. Plans for armed resistance had to be repeatedly modified as the military and political situation changed. The “Storm” [Polish: Burza] plan ultimately adopted anticipated a state of disorganization on the German home front and the authorities of the underground state taking control of the state. Execution of the “Storm” plan began in February 1944; the last stage of the plan was the Warsaw Uprising (August 1st – October 2nd 1944).

The Home Army suffered the loss of some 62,000 soldiers during the occupation, including the loss of roughly 10,000 soldiers in the Warsaw Uprising.

Figures from S. Korboński, Polskie Państwo Podziemne [The Polish Underground State], , Warsaw 2008.

The military branch was organized as a domestic army. The Commander-in-Chief of this army and his regional commanders had all the rights and prerogatives of army commanders with regard to the population of a war zone. They could issue military edicts to guide the behavior of the population, and requisition men for necessary war work. Each soldier in the army had all the rights and duties of a front-line combatant, even including the traditional one that all time spent on the front lines counted double toward all benefits such as veteran’s pensions, priority rights, and civil service.

The Commander-in-Chief, although this was not known to the public, was allocated a special power by a decree of the President. He was authorized to call a partial or total mobilization of all Poles the moment the Polish Government, acting in concert with the other Allied governments, gave the order for an open, universal uprising against the German occupants. The work of the Home Army was divided into two parts: Command included propaganda, political diversions against the occupant, organization for the general uprising, and tasks undertaken in cooperationwith the political and administrative branches; the other was devoted to the daily struggle and included sabotage (activity against the German civil and industrial war machine), diversion (direct activity against the German Army, its communications, supplies and transport), military training, etc. In addition, it collaborated with the units that operated in the areas that had been incorporated by force into the Reich and Soviet Union.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 255-256

READ ALSO

COMMENT

The Directorate of Underground Resistance was founded in early 1943 through a merger of the Government Delegation’s Directorate of Civil Resistance and the Home Army’s Directorate of Covert Resistance. It was responsible for carrying out ongoing sabotage and diversion.

The Directorate of Underground Resistance consisted of: the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Army Gen. Rowecki (and after his arrest, Gen. Tadeusz Komorowski), Home Army Chief of Staff Gen. Tadeusz Pełczyński, Head of the Directorate of Diversion Gen. Emil Fieldorf, Head of the Bureau of Information and Propaganda Gen. John Rzepecki, and the acting head of the Directorate of Civil Resistance, Stefan Korboński.

CITIZENS OF THE REPUBLIC

For four years now, the Polish nation has been fighting the cruelest invader it has ever faced. It has mobilized all available forces in this fight. [...]

For four years now, the barbarian invader has been using the most barbaric methods to purposely and ruthlessly exterminate Poles merely for being Poles. [...]

In order to fight this, WE MUST GIVE OUR ALL AND CHANNEL OUR EFFORTS IN WELL-ORGANIZED AND WELL-DIRECTED ACTIONS. The Polish people must strike back with redoubled blows in response to the increase in terror and oppression by the occupation forces. To this end, THE FIGHT AGAINST THE GERMAN OCCUPATION in Poland by means of underground resistance WILL BECOME THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE DIRECTORATE OF UNDERGROUND RESISTANCE, CREATED BY THE GOVERNMENT’S REPRESENTATIVE IN POLAND AND THE COMMANDER OF THE ARMED FORCES IN POLAND.

WE CALL ON all citizens of Poland to UNCONDITIONALLY FOLLOW THE ORDERS AND COOPERATE IN THE ACTIONS OF THE DIRECTORATE OF UNDERGROUND RESISTANCE, TO SUPPORT IT AND PROVIDE IT WITH ALL POSSIBLE ASSISTANCE – as it is the sole institution possessing the authority of the nation’s legitimate government.

The Directorate of Underground Resistance will be responsible for directing resistance operations and maintaining the Polish people’s hostile attitude towards the occupation forces, for direct day-to-day combat operations against the occupiers, for responding to terror with terror directed back at the Germans, and for retaliation – in response to acts of brutality by the Gestapo.

Well-deserved and severe punishment will also be meted out to those Poles who betray their nation and serve the enemy.

THE SOLE COMPETENT AUTHORITY to adjudicate crimes committed by Polish citizens against the State and its People are SPECIAL COURTS established by the Government Representative in Poland and the Commander of the Armed Forces in Poland. [...]

The Special Courts will rigorously prosecute blackmail and extortion under the cover of “efforts” to free imprisoned or interned Poles, and the blackmail of Jews in hiding. [...]

In our fight against the enemy, an indispensible prerequisite for victory is the need to follow, under threat of penalty, the orders of the Government, the Commander-In-Chief, and their Representatives in Poland.

“Republic of Poland”, No. 11 (62), 1943, in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków. t. II [The True Story of the Poles, Vol. 2], , Warsaw 1999, pp. 1206-1207.

In the ‘fifth branch’ were the loose organizational centers. This branch was an effort to curtail the waste involved in satisfying a desire to give vent to a sense of individuality. An effort was made to co-ordinate the activities of all the political, economic, educational, and religious groups which were active outside the other four branches. Some of them developed aspects which became very important, such as the programs for the continuing clandestine education of primary- and high-school students, as well as instruction at university level. Most of them helped keep up morale, although they lacked the proper technical and financial means to be import ant factors in resistance. These groups constituted what was called ‘the outskirts of the Underground.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 257

READ ALSO

Aid for those in need

REMEMBER THE LEAST FORTUNATE!

We received the following comments from readers, summarized below:

I propose a fixed monthly or weekly tax to benefit the least fortunate of our countrymen: the families of political prisoners, victims of the camps, and the displaced. Especially given the fact that living under occupation we pay no taxes to the Polish State, but only to the German occupation forces. A whole range of people are living today, in spite of repression, in tolerable conditions, and a certain part of society, those with commercial interests, are sometimes living in better conditions than before the war!

These people should be taxed, and taxed immediately, given that our 4th winter under wartime conditions is approaching. It should not be the case that some pay a tax at the alter of the Polish state in blood and lost health and property, while the others profit from business, and from time to time, to soothe their conscience, graciously make a charitable donation of, let’s say... 5 or even 10 zlotys! [...]

Given that some are paying a tax in blood and lost health, others should at least contribute a decent sum of money for the least fortunate, those deprived of family, familial warmth and home!

Start taxing without delay.

“Information Bulletin”, No. 56, 1942, in: Przegląd Wojskowo-Historyczny [Historical and Military Review], R. IV, No. 3 (special edition), Warsaw 2003.

The Education Department of the Underground had reached in 1942, the year when Zosia was to be graduated, an incredible peak of efficiency.2 In the Warsaw district alone more than eighty-five thousand children were receiving tutelage through its offices. More than seventeen hundred youths had been graduated from the high schools. The pupils met secretly in their homes in groups of three or six, for different ostensible reasons, to play chess, for a social visit, to learn a trade. Any common purpose would serve as a pretext. The teacher who came to them underwent a fearful risk. Children are obstinately curious and could scarcely be repressed in their desire to learn the true identity of the teacher, in what school he had taught before the war, where he lived, and other details that it was dangerous to let adults know, let alone children. The safety of these overworked educators depended on the uncertain vagaries of youthful prudence. The unwitting word of a parent or pupil could and sometimes did mean death and bestial torture for these men, a number of whom were caught by the Gestapo in the performance of this invaluable service.

The greatest difficulty that confronted the education authorities was the problem of obtaining a sufficient number of textbooks. After much indecision, it was finally decided to print facsimiles of prewar textbooks so that if they were discovered, they would appear to the Germans as dating before the occupation.

Zosia was due to be graduated in September 1942.[…] To receive a graduation diploma, the applicant had to pass final tests in five subjects, covering the material of a twelve-year course in each. In three of the subjects both oral and written examinations were stipulated. In the remaining two, the kind of examination was elective.[…]

Zosia had done excellently in all her examinations. The diploma she received was merely a calling-card bearing the pseudonym of the chairman of the commission. On the reverse side appeared a few innocent sentences: Thank you for your charming visit on September 29, 1942. I was most satisfied. You told me such interesting things. Bravo.[…].

When Poland is reconstituted after the war, thousands of these cards will be exchanged for official diplomas.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 331-335.

READ ALSO

Communiqués of the Directorate of Underground Resistance on the sentences delivered by the underground courts

COMMENT

he Directorate of Civil Resistance reports: On March 15th 1943, by sentence of the Special Court, FRANCISZEK RUTKOWSKI, a foreman in the Warsaw Municipal Authority’s department of water supply and sanitation construction, was sentenced to death and stripped of his civil rights and privileges. During his trial, it was determined that as a result of Rutkowski’s reports to the Gestapo, weapons were discovered and numerous people were arrested. He was executed by shooting on March 18th of this year.

“Information Bulletin”, No. 12, 1943, in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków. t. II [The True Story of the Poles, Vol. 2], Warsaw 1999, p. 977

The Directorate of Civil Resistance announced the following sentences by the Court of Civil Resistance in Warsaw on December 3rd 1942:

[…]

II. The following artists, formerly of the Polish Theatre in Warsaw, have been sentenced to infamy: 1) Bogusław Samborski, 2) Józef Kondrat, 3) Michał Pluciński, 4) Hanna Chodakowska – all for active participation in the making of the German film “Heimkehr”, containing anti-Polish propaganda and defaming the Polish people and Poland.

III. The following artists, formerly of the Polish Theatre in Warsaw, have been sentenced to receive a formal reprimand: 1) Jerzy Pichelski, 2) Franciszek Dominiak, 3) Józef Woskowski, 4) Stanisław Gorlicki – all for complicity in the shooting of this film; their decision to break their contracts and quit making the film were treated as mitigating circumstances in their cases.

“Information Bulletin” No. 9, 1943, in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków. t. I [The True Story of the Poles, Vol. 1], Warsaw 1999, p. 746.

One of the most important divisions of the Government Delegation was the Directorate of Civil Resistance (Polish: Kierownictwo Walki Cywilnej – KWC).

It was established in autumn 1940 by the Government Delegate and the Commander of the Union for Armed Struggle. Its main task was to disseminate the code of civil resistance throughout the country and to ensure its implementation. The KWC organized and supervised underground justice, directed civil sabotage activities, and operated its own underground network of radio transmitters to maintain communications with the Polish government in London. Throughout its existence, the KWC was directed by Stefan Korboński.

The fourth branch was called the Directorate of Civilian Resistance and its main function was to bolster up the policy of ‘the stiff attitude toward the occupant.’ Its members were outstanding scientists, jurists, priests, and social workers. They were to keep Poland clear of traitors and collaborationists, to try those accused of collaboration, sentence them, and see that the sentence was carried out. It had regional branches which functioned like people’s tribunals of the type that frequently arise in times of revolution or national upheaval.

It was authorized to pass sentences of either ‘infamy’ or death. A Pole was sentenced to ‘infamy’ who did not follow the prescribed ‘stiff attitude toward the occupant’ and was unable to justify his conduct when asked to do so by us. It meant social ostracism, and was also the basis for criminal proceedings to be held after the war. Sentences of death were passed on anyone who attempted active aid to the enemy and could be proved to have harmed the activities or personnel of the Underground. The tribunals also had the power to pass sentences of death on exceptionally vicious German officeholders. There was no appeal against the sentences of the tribunals and they were invariably carried out.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 256-257

READ ALSO

Report on the results of Operation N

Circulation of the “Information Bulletin”

As previously reported, as ordered, work began on “N” in early 1941, with the aim of conducting subversive propaganda activities among the German army and the civilian population in the Reich and among the Germans living on Polish soil. This last aspect is intended to also cause increased chaos in the occupational administration. Work on “N” is being carried out under extreme conditions, however, in spite of this, at least one publication is being printed each week. The contents usually appears to be ”purely German” in character, preventing easy identification of their true source. The publications are often carefully forged official instructions or statements.

“N” publications are being circulated over a wide area. They are reaching the coast of the English Channel and Czechoslovakia, and are circulating throughout Poland, although our main distribution efforts have been directed toward to the Eastern Front.

Internal reports and analysis of the letters of soldiers from the front confirm that “N” publications are reaching the most remote sections of the front and are having an impact on the army’s morale [...]

I have recently been given official pronouncements issued by the Oberkomando der Wehrmacht and the occupational government that demonstrate the Germans’ belief in the effectiveness of Operation “N” and how they are trying to counteract it. These pronouncements confirm conclusively that “N” publications are in circulation on the Eastern Front and that the German organizational apparatus is unable to prevent the publications from reaching the ranks of the army [...].

in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków. Ilustrowane wypisy źródłowe 1939-1944. t. I [The True Story of the Poles. Illustrated excerpts of sources, 1939-1945, Vol. 1], , Warsaw 1999, p. 666

The magazine’s steady increase in the circulation, reaching a level unprecedented in clandestine conditions, 50,000 copies per week, which multiplied the dangers of carrying out clandestine print and circulation activities.

The moral obligation of each reader was to share each copy of the bulletin he received to friends who did not receive it, making sure to take the necessary safety precautions.[...] Maintaining the safety and security of the Underground press and those who selflessly distribute it is in your hands, dear reader.

“Information Bulletin” No. 47, 1943, in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert Prawdziwa historia Polaków. Ilustrowane wypisy źródłowe 1939-1944. t. II [The True Story of the Poles. Illustrated excerpts of sources, 1939-1945, Vol. 2], Warsaw 1999, p. 1384.4.

The secret press in which I participated did not deal exclusively with internal affairs and party matters. Every paper – daily, weekly, bi-weekly – brings first of all news to its readers. The news of the world was supplied by a large and well-organized chain of secret radio listeners. Risking their lives constantly, young and old, men and women, listened to foreign broadcasts in soundproof cellars, in small huts set up in forests, in attics with faked double roofs. The London BBC, Boston’s WRUL, and Columbia’s WCBX (New York) were the major sources of information. Every paper had several listening stations, for one could never be sure whether the American and British broadcasts would be heard, or whether one would be able to listen to one at the necessary time. Young boys took the messages to the ‘city desk’ in the basement or hut in the woods, where the one man serving as editor and printer worked on his hand press or mimeograph. He wrote the editorials; he received messages from ‘correspondents’ and ‘reporters’ spread all over the country who transmitted to him by messengers news about what was going on in the country itself.

Special press agencies had been organized by the Government Delegate, the military organization and the staffs of the large political parties. Through these, Poland received truthful reports of the latest news from the outside world, the battlefronts and the most important occurrences in the occupied countries. These press serviceshad regular correspondents in neutral and Allied countries.[…]

The newspapers themselves were numerous and heterogeneous in character. Every political group had at least one secret organ and many had several. The influence and circulation of these papers were as diverse as the conflux of political and social opinions of which they were the expressions. The Information Bulletin, the semiofficial organ of the Underground Army, had a circulation of at least thirty thousand copies and was even greater when one considers the known fact that each copy had a plurality of readers. The circulation numbers of the others were less significant, ranking from one hundred and fifty to fifteen thousand. […]

Publishing a successful underground newspaper required men who were thoroughly trained and competent, not merely to produce effective journalism but to make sure that nothing of importance was revealed to the enemy.[…] The Government Delegate had his own official organ, Rzeczpospolita Polska (The Polish Republic), chich expressed the official point of view of the government-in-exile and the underground authorities. […]

Wiadomosci Polskie (Polish News) was the official organ of the Commander of the Home Army. It contained articles devoted to social and military problems.[…]

The military command also issued Zolnierz Polski (The Polish Soldier), a large part of which was devoted to reminiscences and analysis of the military defeat. It published, too, news of the activities of the Polish Army at home and abroad.[…]

Besides periodicals, the secret press published books and pamphlets of all kinds. The pamphlets were mostly ideological. The books were chiefly reprints of works the Germans had forbidden – Polish classics, texts for underground education, military works, and prayer books.[…]

The secret press was the means by which the underground state kept in direct contact with the large mass of the population. Through it, the people were constantly kept aware of what was being done so that their morale and hope were kept at a high pitch. For their work to be successful, the underground organizations required the knowledge, too, that the people had faith in them and supported their authority. Testimony to this effect was received in many ways.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, Warszawa 2004, p. 287-298.

The work I did here was quite different from any I had done before. Because I knew languages and something of international affairs, besides having a well-developed memory, I received a new assignment. My duty was to listen to radio reports and to take them to the highest authorities in the Cracow civilian and Military Underground. I was not supposed to listen to Polish broadcasts from London nor to English propaganda, but to those from neutral countries like Turkey, Russia (before Russia, herself, was at war), Sweden and, if possible, America. My superiors were anxious to have a true and realistic picture of the total military and political situation. In order to provide this, it was essential not to rely solely on broadcasts in English, French or Polish that came from the Allies’ radio stations, whose content, far too like ‘propaganda,’ needed to be reviewed by using the news and analysis from military and political commentators in neutral countries. If pessimistic or discouraging, my reports were treated as secret material and were used only by our leaders. More often, however, the reports

I handed in were used as the basis of foreign news articles in the Cracow underground press.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 251.

I had got somewhat more than I bargained for when I asked Lucien for propaganda work. I had not yet fully recovered from my illness and the simple projects I had embarked upon had mushroomed into ambitious efforts that required a considerable expenditure of energy. The nucleus of the program had been simply to contribute some spadework toward sustaining the morale of the Polish population and bringing retribution on the heads of pusillanimous or treacherous collaborators. But each idea seemed to sprout new ones that could not be neglected without a vital injury to the entire growth. I found myself,with the consent and aid of the Underground, involved in a largescale production of letters, leaflets, and, finally, of periodicals and newspapers. I had the responsibility of preparing the texts for a wide variety of propagandistic forays. It was at once a delicate and exciting venture into literary and political realms. The lines of each text had to be traced out with minute precision, for nearly all our documents were displayed as the products of secret German organizations, Liberal, Socialist, Catholic, Communist, and even Nazi. It was a cardinal principle of our propaganda technique to issue all our exhortations, proclamations and even news reports under the aegis of a fictional body which espoused the Catholic ethos, the traditions of German parliamentarianism, international labor solidarity, or individual liberty. Each piece had to be written In scrupulous conformity with the tenets of its purported sponsors.

After a while, I began to feel like an overworked actor in a povertystricken variety company. I was constantly on tenterhooks for a single slip could easily give away the whole thing.

The policy of issuing propaganda under German auspices was attended by increasing success, greater daring and, as a consequence, more ambitious projects that were constantly enlarged in scope. The Underground ultimately established two newspapers that circulated not only in the ranks of the German Army in Poland, but quite widely in the Reich itself. One was a presumptive organ of the German Socialists, the other an ardently nationalist sheet.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 235-236

READ ALSO

About "small sabotage"

The Anchor

Renaming streets

10 Commandments For Civil Resistance

[...] There are, however, some forms of sabotage that, at the moment, are not only acceptable, but even demanded. Each of us – every man, woman, and young person, those working in organized groups or on their own – each of us must take active part in the campaign of “small” sabotage. This sabotage does not expose anyone to harm, but it makes daily life difficult for the occupation forces.

Here are some examples of “small” sabotage: 1 Working slowly to increase the time it takes to perform any work in your profession requested by a member of the occupation forces. 2. Making various “mistakes” in work commissioned by the Germans. 3. Giving false information to Germans asking for directions (wasting their fuel and time). 4. Answering “I don’t understand” during any attempts to make contact, not making use of any German services, such as trains, trams (this creates a feeling of unfriendliness & hostility). 5. Disregarding all German regulations, laxly implementing them, putting them off until the last minute, etc. 6. “Tricking” the Germans in various ways (anonymously denouncing zealous Volksdeutsche to the Gestapo, posting anti-German poems, aphorisms, and jokes on advertising poles or “unowned” fences. Putting our minds to work a little will allow each of us to find more and better examples to add to this list, as well as to come up with new ideas.

It is clear that the wide-scale and daily use of a “small” sabotage will make the enemy’s stay in occupied territory tedious and unpleasant. [...]

“Information Bulletin”, November 1st 1940, for: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków. t. I [The True Story of the Poles, Vol. 1], Warsaw 1999, p. 280

The Anchor

A month has passed since an anchor is being drawn on the walls of Warsaw. The symbol is drawn so that the upper part forms the letter “P” and the lower part the letter “W.” A number of these drawings explain that the anchor is the symbol of Polska Walcząca [“Fighting Poland”]. Although it was started by some sort of group, it has become common property. Erased from these walls every day, it shows up every day once again, drawn by thousands of anonymous hands. There are streets where you don't see as many, but then there are some where you see it on every building, lamp post and sidewalk... We cannot explain the popularity of this symbol. Perhaps it is the will to show the enemy that despite everything, he has not broken our spirit, that we are here, just waiting for the right moment. Perhaps the people drawing the sign are influenced by the anchor's significance – a symbol of hope and reliability? Maybe it was the perverse will to overpower the enemy swastika, by our own, Polish symbol? One way or another, the sign of the anchor has taken over the capital and it is possible that it will take over the country. Have it go on into the world! May it trouble the enemy and show that Fighting Poland is alive and vigilant.

A few days ago on the streets of Warsaw, many street names were changed at the hand of the Polish Underground.

This is undoubtedly a kind of demonstration to mark the fourth anniversary of the September campaign.

We noticed the following renamed streets: Jerozolimskie Avenue – Gen. Sikorski, Bankowy Square – Starzyński Square, Washington Circle – Roosevelt Square, Zieleniecka Avenue – Churchill Avenue, Wronia Street – Niedziałkowski Street, Wspólna Street – Polish Underground Street, Graniczna Street – Defenders of Warsaw Street, Rogowska Street – Jan Kryst Street, Zielna Street – Defenders of Westerplatte Street.

“Information Bulletin”, No. 39, 1943 for: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków. Ilustrowane wypisy źródłowe 1939 – 1945, t. II [The True Story of the Poles. Illustrated excerpts of sources, 1939-1945, Vol. 2], Warsaw 1999, pp. 1278.

1. Poland is fighting its enemies, not only abroad, but also on the country’s presently occupied territory.

2. Until the start of armed fighting – war will be expressed on Polish territory through civil resistance.

3. Participation in civil resistance is the duty of each and every Polish citizen.

4. The main requirement of this obligation is respecting the legitimate Polish government-in-exile, and following the orders of its authoritative bodies in Poland.

5. Civil resistance against the occupation forces demands that we boycott their orders and summonses, obstruct their every action in the areas outlined by the leadership of Polish life, and absolutely avoid contact for purposes of trade or cultural or social relations.

6. It is necessary to maintain social solidarity, and to support your fellow Pole whenever he is threatened with physical or material harm.

7. You should maintain the highest sense of national honor, and act in accordance with this honor.

8. You should prevent any deviation by a Pole from these rules of conduct, to which he is bound, by means of persuasion, exhortation, social boycott, and finally, noting these criminal acts and reporting them to the proper Polish authorities.

9. Turncoats and renegades must be boycotted, like the enemy, and must be reported as traitors.

10. The duty of every Pole is to demonstrate concern for the survival and preservation of Polish culture in all its forms – human, cultural and material – as a necessary force for securing freedom and rebuilding the country.

Poles! The degree to which you obey the above rules and orders will be a true test of our civic values for future generations. Remember that in future times of freedom, we will all have to account for our choices and actions today.

Source: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków [The True Story of the Poles, Vol. 1], London 1999, p. 560

‘The Little Wolves’ was an organization of young boys formed under the leadership of some ‘Experts’ for the purpose of harassing the Nazis directly, annoying the occupants, poking fun at them, working more sharply on their nerves by diverse stratagems. The members of this organization were the authors of a large share of the millions of inscriptions that became the most common flower of Warsaw, and bloomed afresh each morning. They painted signs like ‘Poland fights on’, or ‘The punishment for Oswiecim is near’ or ‘Hitler Kaputt’ with indelible paint on German trucks and automobiles, on German residences, and quite frequently on the backs of the Germans themselves. An epidemic of flat tires on German vehicles resulted from the Little Wolves’ thorough and systematic sprinkling of the streets with broken glass, bits of barbed wire, and any other pointed objects on which they could lay their hands. They festooned the city with caricatures and posters which were constant sources of amusement to the population of Warsaw. The mischievous and diabolically efficient little pack did much to sustain the psychological atmosphere of contempt for the Germans and fostered the spirit of resistance. In the fall of 1942, when the Germans requisitioned all of Poland’s furs and wools for the Eastern front, the Little Wolves got up a brilliantly executed series of posters on the topic of the day. A gaunt, gloomy German soldier was depicted swathed in a very feminine mink coat with a silver-fox muff protecting his hands. Underneath were captions on the order of ‘Now that I am so warm, dying for our Führer will be a pleasure.’[…] The Germans had destroyed all the monuments that commemorated Polish heroes or patriotic events. By common consent all Poles made conspicuous detours around the spots where these monuments had been located. Prayers would even be offered up at these spots, to the outrage of the German officials. The Little Wolves used flowers as a symbolic message. They were found in profusion where the monuments had been. They scattered them wherever a member of the Underground had been executed or even arrested, in locations where some particularly heinous German crime had been committed. Nothing could stop the Little Wolves and their exploits were innumerable, sharp thorns in the sides of the occupants.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 327-328

READ ALSO

COMMENT

The Underground state administration was modeled on the structure of the pre-war government. The role of the Office of the Government Delegate for Poland (the government) and the departments under it was to maintain the continuity of the state’s institutions, to ensure the proper functioning of the Underground state, to be prepared to take control of the country after independence, to protect and salvage cultural property, and to document German crimes. The Budget and Finance Section directed funds received from the government. Its task was to finance the activities of the delegation and the organizations associated with it (such as the Council for Aid to Jews). The Department of the Internal Affairs organized and directed the secret state administration throughout the country. The task of the Department of Information and Press was to provide truthful information and create an official press for the Underground government. The Department of Education and Culture was responsible for organizing clandestine schools, and preparing curricula and exams for them. The Department of Labor and Social Welfare looked after political prisoners and their families, provided material aid to those of particular value to society, such as scientists, professors, writers, and artists.

Other departments included the Department of Industry and Commerce, Department of Agriculture, Department of Justice, Department of Liquidating the Effects of War, Department of Public Works and Reconstruction, and Department of National Defense.

In addition to their ongoing activities, all departments were responsible for preparing the personnel, plans and regulations necessary to assume control of relevant ministries after the country’s liberation.

Jan Karski About Secret Polish Administration

In accordance with the principle that the underground movement was the means through which the Polish state operated inside Poland, the central organization had now been divided into five branches. The administrative branch was composed of the Chief Delegate of the Government and the Regional Delegates. Under their supervision twelve departments functioned, each one of which had a director who was the counterpart of a Minister of the Polish government-inexile, now in London, such as the Director of the Interior, Treasury, Education, etc.

The primary duty of this branch was to organize and maintain the autonomous and secret deputy administration of the country. The attitude of ‘not noticing the occupant’ had prevailed. The Poles had refused any part in the political administration of the German General Government and the edict had been issued that not a single law or decree of this agency was to be obeyed.3 The result would have been a condition of chaos, and the authority of the Secret Deputy Administration was established to bring control over the country. This administration exercised compulsion on the populace to a much greater degree than the Nazis could with all their brutal measures. In each county, city, and community, there was an official who, invested by the full authority of the state, issued decrees, and contacted the people. These persons were also designated to be ready the instant the country was cleared of the invader, to take over as a complete, democratically chosen administration, fully capable of managing the affairs of the country.

J. Karski Story of a Secret State, p. 254 -255

READ ALSO

KWP Statement on underground diversionary operations

The first statement of the Directorate of Underground Resistance on the diversionary operations of the Home Army, “Republic of Poland”, No. 1, Warsaw, January 12th 1943.

As part of self-defense operations to support the displaced population in the Lublin region, on the night of December 31st, 1942, a series of diversionary acts of sabotage were carried out, namely: four railway bridges were blown up, two trains were derailed, substation and telecommunications equipment was destroyed in several places, and several housing settlements, intended for German settlers, were burned down.

in: D. Baliszewski, A. K. Kunert, Prawdziwa historia Polaków. t. II [The True Story of the Poles, Vol. 2], Warsaw 1999, p. 846.

DIVERSIONARY ACTIVITIES

The work of the Home Army was divided into two parts: Command included propaganda, political diversions against the occupant, organization for the general uprising, and tasks undertaken in cooperationwith the political and administrative branches; the other was devoted to the daily struggle and included sabotage (activity against the German civil and industrial war machine), diversion (direct activity against the German Army, its communications, supplies and transport), military training, etc. In addition, it collaborated with the units that operated in the areas that had been incorporated by force into the Reich and Soviet Union.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 255-256

READ ALSO

General Stefan Rowecki on the results of sabotage operations

MESSAGE SABOTAGE – DIVERSION

on July 1st

[...] 153 locomotives and 561 wagons were damaged. Incendiary materials were placed in 25 transports. Sixteen transports were confirmed to have burned, including 4 with ammunition. The brakes were removed from 19 trains. Overall, this resulted in the interruption of East-West traffic 34. Forty two tons of gasoline, 20 [tons of] oil, and 85 automobiles were destroyed. In one tank factory, eight machines and two conveyor belts were damaged. Bolt threads are being damaged in an ongoing fashion. The completion of components for submarines has been delayed. In one arms factory, the main machine tool was damaged for three weeks. In a machine tool factory, one machine tool was damaged and one oil tank was contaminated. [...] In a train car factory, seven transmission belts were destroyed and grease for the turning machine was contaminated. In an iron foundry, more than 54 casting moulds and finished castings have been destroyed [...] In a steelworks, 25 tons of steel casting was destroyed. A gas pipeline was halted for 25 hours, resulting in an open-hearth furnace going cold. [...] In one aircraft production plant, 25,000 rivets and numerous tools were destroyed. A fire was set at one power station and 1 railway production facility. Poison was used 194 times, and seven train coaches were contaminated.

Losses: Two killed by gunfire, six injured; and two arrested.

Kalina

in: Armia Krajowa w dokumentach 1939-1945, t. II [Home Army in Documents 1939-1945,Vol. 2], Szczecin 1989, pp. 291-292

ORGANIZED MILITARY SABOTAGE

The work of the Home Army was divided into two parts: Command included propaganda, political diversions against the occupant, organization for the general uprising, and tasks undertaken in cooperationwith the political and administrative branches; the other was devoted to the daily struggle and included sabotage (activity against the German civil and industrial war machine), diversion (direct activity against the German Army, its communications, supplies and transport), military training, etc. In addition, it collaborated with the units that operated in the areas that had been incorporated by force into the Reich and Soviet Union.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 255-256

READ ALSO

Operation Kutschera

Operation Kutschera, “Information Bulletin”, Warsaw, February 10th 1944

KUTSCHERA PAID WITH HIS HEAD

SS and Police Leader in the Warsaw district Franz Kutschera was assassinated by members of the Polish Underground. Kutschera had been responsible for stepping up terror measures by the Germans in the capital and the district over the previous four months, and in particular for “retaliatory” mass street executions. Since mid-October, approximately 1,400 people had been officially executed in Warsaw alone; in fact, a smaller number of Poles were also shot on the streets of Warsaw in 36 additional executions, with part of the killing being carried out in secret within the walls of the former ghetto.Overall, however, the Germans killed several times this number during this period in Warsaw – 4,000-5,000 people!

Kutschera was killed on Ujazdowskie Avenue in front of his office. In addition, his German driver and two guards were killed, and an aide-de-camp was seriously wounded. The assassins, travelling in cars, fled in different directions* […]

“Information Bulletin” No. 6 (213), 1944, in: Przegląd Historyczno–Wojskowy [Historical and Military Review], IV, No. 3 (special edition), Warsaw 2003.

* Four Home Army soldiers were killed in the operation

The military branch was organized as a domestic army. The Commander-in-Chief of this army and his regional commanders had all the rights and prerogatives of army commanders with regard to the population of a war zone. They could issue military edicts to guide the behavior of the population, and requisition men for necessary war work. Each soldier in the army had all the rights and duties of a front-line combatant, even including the traditional one that all time spent on the front lines counted double toward all benefits such as veteran’s pensions, priority rights, and civil service.

The Commander-in-Chief, although this was not known to the public, was allocated a special power by a decree of the President. He was authorized to call a partial or total mobilization of all Poles the moment the Polish Government, acting in concert with the other Allied governments, gave the order for an open, universal uprising against the German occupants. The work of the Home Army was divided into two parts: Command included propaganda, political diversions against the occupant, organization for the general uprising, and tasks undertaken in cooperationwith the political and administrative branches; the other was devoted to the daily struggle and included sabotage (activity against the German civil and industrial war machine), diversion (direct activity against the German Army, its communications, supplies and transport), military training, etc. In addition, it collaborated with the units that operated in the areas that had been incorporated by force into the Reich and Soviet Union.

J. Karski, Story of a Secret State, p. 255-256

READ ALSO

COMMENT

The Polish National Council was established in France by decree of President Władysław Raczkiewicz in December 1939, as a consultative body to the President and the Polish government-in-exile. It included representatives of political parties (the National Party, Peasant Party, Polish Socialist Party, and Labor Party) as well as non-party members and representatives of the Jewish population.

Joint talks of the government and the National Council of Poland

Source: NATIONAL DIGITAL ARCHIVES

Pursuant to Article 79 paragraph. 2 of the Constitution, I proclaim the following:

Article 1. For the duration of exceptional circumstances resulting from war, I appoint a National Council to act as an advisory body to the President of the Republic of Poland and the Government.

Article 2. The President of the Republic of Poland shall convene, open and close sessions of the National Council.

Art. 3.1. The National Council shall issue opinions on all matters submitted by the government during its sessions.

Art. 3.2. The Government shall in particular submit the state budget during a session of the National Council. The National Council can also express its opinion in the form of suggestions concerning the need to issue certain decrees and regulations.

Article 4. The National Council may also, both at the request of the government and on its own initiative, consider issues concerning the future political system, in particular, the law on elections to Legislative Bodies. [...]

Article 9. National Council resolutions are to be passed by a simple majority vote in which at least two-thirds of the council’s members participate. [...]