| Author's Trip

| The Overall Situation in the Country

| Jewish Questions at Home

| A Brief for the Polish Government

| Sustaining the Spirit of Combat in Polish Society

| An Account of Karski’s Conversation with President Roosevelt

Author's Trip

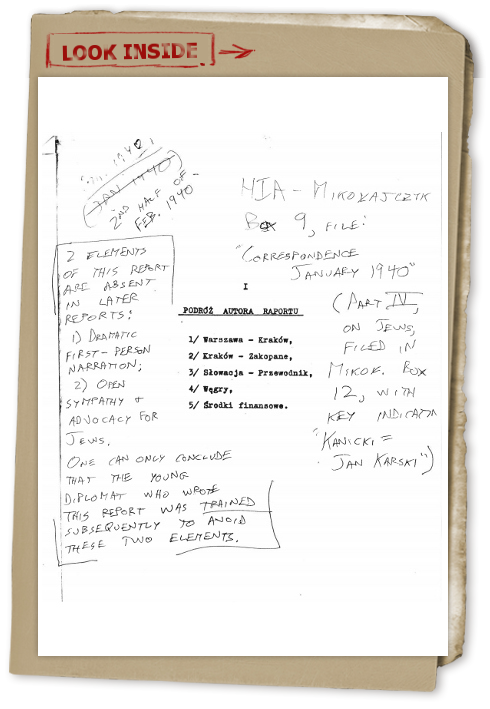

Handwritten:

- Warsaw-Krakow

- Krakow-Zakopane

- Slovakia. Guide

- Hungary

- Financial Resources

REPORT ON THE AUTHOR'S TRIP FROM WARSAW TO PARIS

Warsaw-Krakow

I left Warsaw around January 20, 1940. I left the country on January 29, 1940. From Warsaw I went to Krakow. Because Poles are forbidden to travel by express trains, not even second class, the trip lasted almost two days.* Poles can't travel on these trains because the route leads right next to Zawiercie, next to territories incorporated by the Reich, and thus Poles need special passes or passports to get from Warsaw to Krakow. Because I did not have such a pass, I had to go in the Częstochowa direction, then to Kielce and, after a few hours' wait, to Krakow.

The trains are full. The passengers are primarily 1) food salesmen 2) people living in the General Government traveling from larger cities to the country to buy food, clothing, wood to burn etc. 3) Jews.

When it comes to the Jews, it needs to be emphasized that they are forbidden to change, even temporarily, their permanent residence without special authorization from the Gestapo.

The trains are largely unheated, without lighting, sometimes without windows. At the stations you can't even buy tea with sugar, there are no confectionary products [sweets or pastries], vodka, alcohol, coffee. The mood on the trains is depressing, the passengers are tired, impatient, ruthless and unforgiving. If there is any conversation at all, it is about the war or food. Everybody is complaining, cursing the former government and regime, they feel abandoned by the intelligentsia** and their social, cultural, political, religious leaders and role models. Everybody is bitter, often despondent. The attitude towards Jewish passengers is merciless, ruthless. They are often pushed out of their seats, threatened, taunted.

The Jews are behaving passively, submissively. The stations, both large and small, are full.

In general, the territory of the General Government leaves the impression of an area in which the population is in constant flux.

Almost everybody is looking for somebody, or would be happy to find somebody; everybody is trying to reach somewhere, buy something, sell something, arrange something, etc.

Traveling on the General Government territories actually doesn't require any passes. In practice, however, people who want to undertake a further trip – Warsaw – Zakopane, Lublin - Krakow, Krakow - Tarnow acquire documents with some sort of proof saying that their trip is justified and permitted by the German authorities. Taking these precautions is a result of the ubiquitous terror on the Polish territories.

I stayed in Krakow for two days in order to take care of several matters of a political nature.

Krakow-Zakopane

From Krakow I went to Zakopane, where a guide, who lived there, was supposed to take me through the border. The hotels in Krakow and the pensions in Zakopane are not well-occupied [because most lack documents, except K], so having certain documents and an alibi for travel, I lived in the hotel Pod Zlota Roza in Krakow on Florianska Street. I have determined, beyond any doubt, that while I was gone, my backpack was examined. On the route from Krakow to Zakopane, the train was practically empty. There were no tourists. Zakopane was almost empty. The only guests are the families of the German military, brought from the Reich.

In Zakopane I stayed a few days, learning how to ski, because I would pass the border on skis, through the Beskidy Mountains.

*while normally, it should have taken not more than a few hours

**intellectual elite

SLOVAKIA – Guide

The trail which I followed to Slovakia (Poprad) ensured almost absolute safety, for the price of a very cumbersome trip (two full days in completely wild high-mountain areas). The guide, a Polish ski instructor who lives in Zakopane, emphasizes that his job is motivated by conviction, nevertheless, he makes me pay quite a bit (250-500 zlotys). He works for the nationalist political circles. I am referred to him by – and - . Recently, he also started helping the socialist democrats from Krakow.

He is a great skier, knows the route, while providing great safety. Aside from that he's pretty inaccurate and careless when it comes to the rest of the route (Slovakia) and very greedy for money. His name is -.

The Slovak [guide] failed me in part because I didn't have any Slovakian currency. I had to travel on my own, relying only on my experience. I sold some valuables (a watch, ring, wedding band) and either by walking or by bus I got to Dobrzyna, from where I went to the border during the night. The Slovaks are friendly to Poles. They feel badly for us. They don't think they [actually] got their independence. They are scared of the Germans. They believe that the Germans will lose.

Everybody dislikes - or even hates - the Czechs. Those who live in the southern territories want to be under Hungarian rule. The Slovak's friendliness to the Poles was proved by the fact that they gave me help, information and advice, and nobody informed on me or failed me.

I spent two days in Slovakia. I talked to several Slovaks. At one point, I ran out of money. I got on a bus and I had the following conversation with the conductor (there were no other passengers).

-Are you a Catholic? - I asked.-Yes.

-Do you believe in God?

-Yes.

-Are you an honest man?

-Yes.

-So I'm lucky – I said- Sir, I am a Pole, in despair, without a homeland, in a foreign country, without any money. I believe that a Slovak won't hurt a Pole. I am running from a country which is destroyed, plundered, despaired, hurting. I am going to Hungary. Please help me. I believe that not only will you not betray me, but you will also tell me how to get to Hungary.

As a result of this conversation, the Slovak gave me so much help, including information on how to get a driver who would take me to the border in Dobrzyna, and he wished me safe travels. He said he felt sorry for the Poles. He asked me not to say anything, because he was afraid of the Germans and the Hlinka Guard [the Slovakian militia on Nazi orders].

There was no German military in Slovakia at the time (January 30- February 1, 1940) , but the roads were strategically being cleared from snow by German facility workers and trucks with plows.

The Gestapo was functioning. The Hlinka Guard is officially loyal to the Germans. In reality, the Germans aren't popular, but they are feared. The Slovakian nation believes that Poland was betrayed by its leaders and the government, and they feel sorry for Poland.Hungary

In Hungary I voluntarily turned to the authorities. I showed them my diplomatic passport and after a long back and forth, they allowed me to travel freely to Budapest.

They gave me a free train ticket. In Budapest I checked in at the Polish diplomatic mission. They decided to send me to Paris, as a volunteer for the Polish Army. Only in Paris was I to reveal that I came for something else. Mr.-- gave me an appropriate explanatory letter for the Polish military authorities. We used this procedure out of precaution and because it was the easiest. I came to Paris under another name, as Jan Kanicki.

Financial resources

I acquired the funds for the trip from Warsaw to Budapest from several sources: Mr. Konrad, who gave me less than 100 zlotys; Mr. Borowski who gave me a 100 zloty bill; families of three friends who were prisoners in Hungary gave me a ring, a watch, a wedding band, a silver and gold-plated spoon, a silver knife part, so that I could sell these items, and then send the money to their relatives in POW camps in Hungary.

I would like to note that at the diplomatic mission in Budapest when I asked for a reimbursement of these funds, I was told that there are no resources available, but I would surely get the sum back in Paris.

I ask for these funds because the money that I acquired on the road for these items was not my property and I have to send it to the people it was meant for, as I promised their families. The sum is approx. 150 pengo, or 1000 French francs.

Handwritten: Top Secret, to be returned.

Karski's loose, [verbal] account

Italics – COURTESY OF TOM WOOD